Imbarcare il condition monitoring: la sfida della manutenzione predittiva nel trasporto marittimo

In the many articles of our magazine that have addressed the topic of being able to analyze the “warning signals” of possible failures or anomalies, the target was usually an industrial context, with its civil infrastructure in multiple applications, its team of dedicated personnel, and the systems surrounding its numerous assets. The majority of proposals coming from various service companies address these realities, who compare different technical and commercial offers (evaluating costs/benefits, safety, impact on current production…) and then choose the most suitable strategy for their context. With the right space dedicated to the training and satisfaction of field personnel, who will physically carry out the project.

On the other hand, when it comes to managing a ship with a “predictive” perspective, we face even more complex challenges; in addition to what has already been highlighted, safety plays a decisive role in all maintenance choices. By convention and consolidated tradition, even if a vessel (from small coastal shipping to XL oil tankers) is the result of careful designing, it must pass numerous checks made by one or more certification authorities upon entry into service to confirm its “structural robustness” and suitability for use on the planned routes.

These institutions will monitor it throughout its useful life, checking the main infrastructures, going into the smallest functional details, to avoid possible failures that could trigger significant environmental disasters.

Almost all our metropolises have been developed near rivers, lakes or seas, because it facilitated the transportation of large loads of construction materials with a minimal waste of energy, thanks to the low friction offered by the water. A raft pulled by oxen allowed the transport of tens of tons of precious stones or marbles, for the construction of a majestic cathedral, with a minimal waste of energy. The gentle blowing of the Trade Winds has allowed for favorable exchanges between Europe and the “New World” for centuries, just as other impressive currents and various “trade-winds” have pushed merchants, or migrants, through other challenging routes, weaving a network of commercial exchanges involving the entire globe. In the past – before the industrial revolution – ships were designed and built using precious, selected woods, which after a long seasoning took the desired shapes to craft a solid vessel born to face heavy atmospheric events; because they mainly moved through their sails. Propelled by the wind. So the stronger the winds were (depending on the size of the sailing vessel in question) the faster the precious cargo stored inside the hold would reach its destination. The maintenance of such artisanal marvels was continuous, linked to the physiological wear of the components, all “green” by necessity. That is, mostly derived from vegetable cellulose; mainly hemp, blocks and other mobile rigging, wooden planks for the main body. Some wood, in barely rough-hewn shapes, was held on board as a possible spare part (the only redundancy allowed), to be adapted and shaped for the specific need when necessary. For over a millennium, shipbuilding techniques and consequently the various maintenance strategies have remained practically unchanged. The outlines of the boats, which were initially given a “pot-belly” shape, started to become increasingly sharper, while the number of masts and sails consequently increased, pushing these “woods” at very respectable speeds. Corvettes, Frigates, Large vessels, with an increasing number of decks (and guns), became the most popular silhouettes found in marinas or ports (well represented in the paintings of the time), which at the same time grew in size to accommodate the growing importation of exotic goods. Nowadays, the Navy career still features the rank of Corvette Captain, followed by Frigate Captain and ultimately Vessel Captain, a non-trivial achievement for a Navy officer.

Even the many corporate administrative references, for example the classic limited partnership, derive from the era of the first commercial exchanges of vessels (carracks, caravels, tartans…) that sailed towards the outposts of late medieval European civilizations. Discovering new markets and the possibility of very profitable exchanges. From which the “Accomandante” (who embarked with the role of captain) and the Accomandatario, two different roles in which one risked his life, sailing towards the unknown, and the other one risked his capital (business risk), investing in such expeditions that were seldom successful. But with very profitable margins; not only gold, at that time even spices were a valuable stock exchange!

Today’s merchant traffic (responsible for transporting approximately 90% of goods worldwide) moves thanks to an immense fleet of ships whose propulsion is based on several electric motors or generators (including aeroderivative TGs of various sizes), directly or indirectly connected to one or more propeller shafts that allow for very respectable speeds. What in the past was an almost empty hull, the hold, to be filled with bulk goods, today is a concentration of technologies that, in addition to ensuring speed and route according to programs shared with the shipping company, provide for the movement of the cargo (containers of various sizes and shapes) in conditions of maximum safety. The “motorways of the sea” are invisible to the naked eye, but are very evident on the control panels that process GPS signals in real time. They are in turn linked to various control towers (not much different from air traffic towers) located near the nerve centers, thanks to the various transponders installed on the units themselves. It follows that, practically from the moment of departure, the hull becomes a “living organism” whose energy must be continuously produced by a series of generators powered by diesel fuel (more or less purified) to maintain efficiency of all the various on-board functions.

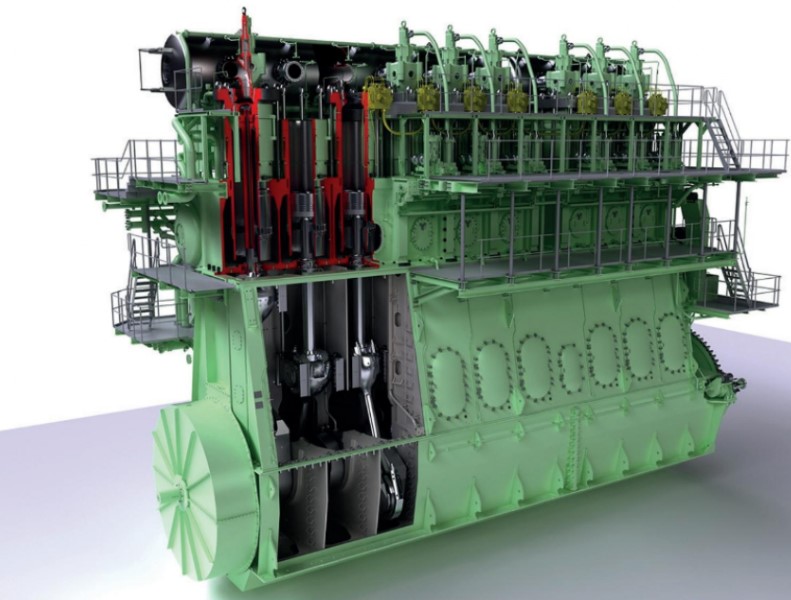

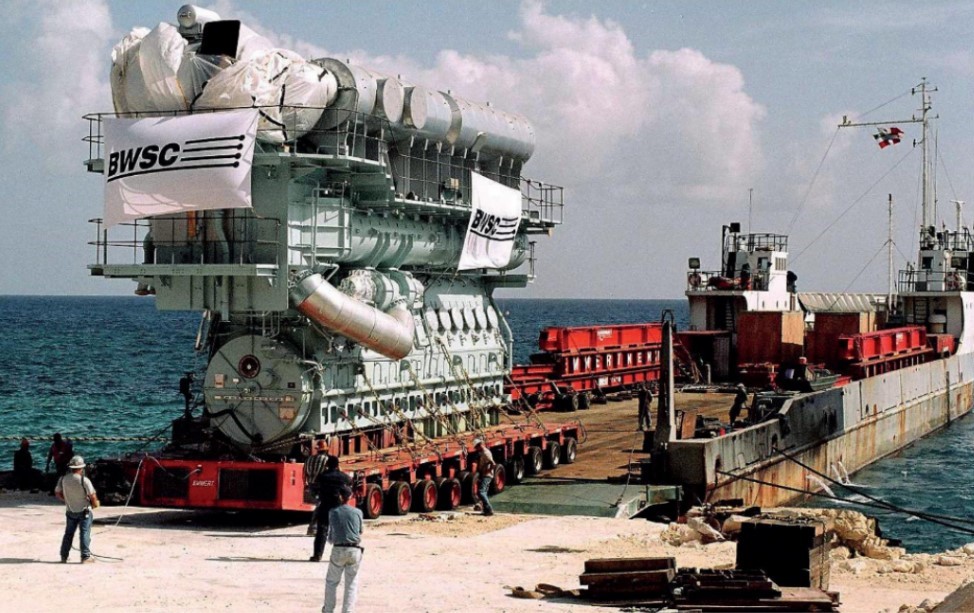

Even though there are several pilot projects to reduce the impact of maritime transport (which, although is less annoying than road transport, partly due to being out of the population’s sight, still interferes with fragile marine ecosystems), including ships that use photovoltaic power or even auxiliary sails that are raised when the wind blows from a favorable direction… hydrocarbons are still the basis of combustion and consequently of propulsion. We are talking about immense tanks below the waterline, storing hundreds of tons of fossil products (coal has practically disappeared, replaced by fuel oil with variable sulfur content or highly refined diesel, depending on the use). In order to operate safely, we need the most suitable lubricants for the purpose, according to the specifications of the manufacturers. As well as a few tons of products distributed in various tanks, easily accessible in order to replenish the right amount of lubricant whenever necessary. Large naval engines, that are ultimately a “magnified” replica of the ones in our cars, with bores measuring 1500 mm or more, are necessarily very slow (a few hundred revolutions) but reach very high powers, up to thousands of horsepower. The quantities of lubricant in play are consequently significant; and generally, lubrication would be constant. We rarely think about replacing the oil, since it participates in combustion (in many cases it is a true “two-stroke” cycle) both directly and indirectly. Therefore, we witness a continuous replenishment of the lubricant charge, a bit like in an old-style scooter.

The by-products of the combustion of such large quantities of fuel, generally with a high or medium sulphur content, lead to the accumulation in the oil of very aggressive acid radicals (SO2-SO3-NOx) that – if not inhibited – could quickly cause significant damage to the entire “hot part” of the system. This is why the formulations for maritime “heavy duty” use provide for the addition of very important basic packages. Monitoring the level of “BN” or base number (residual alkalinity) still present in the fluid has a notable diagnostic value. Traditionally, this measurement is obtained through titration in the laboratory; nowadays, user-friendly tools such as Fluidscan are also available and can be easily used while on board the same ship by non-specialist personnel. Obtaining timely and repetitive measurements. Even the percentage quantity of fuel – unburned fractions – accumulated inside the lubricant can be a valuable indicator of potential risks, linked to the self-ignition of the contaminated oil. Resulting in serious fires or explosions in the engine room. In the past, a device was used to measure the “flash point”, creating the controlled conditions for the ignition of a small volume of oil. The famous “Cleveland”. Which however released pestilential fumes into the environment, whose presence is unfortunately long-lasting. Even in this case, technology has managed to create a small instrument, “FDM-Fuel Dilution Meter”, that can precisely measure the percentage of unburned materials present in the oil without creating any emissions or risk for the operator.

These are just a few examples of how modern technology is able to meet the needs of a fleet manager, who with an investment in equipment and, above all, with the right training of on-board personnel, can monitor the strategic parameters of a merchant ship’s main engines during navigation, without having to wait for a stopover in a port and the inevitable delay in delivering reports, to understand “if” there is a possible risk of failure. Further in the magazine you will find a nice description of the maintenance practices of ACTV. The company whose fleet of over one hundred iconic “vaporetti” ply the waters of the Venice lagoon in very challenging conditions. The current “predictive” strategies are aimed precisely at safeguarding this service in conditions of great management safety.

Rivista Manutenzione & Service